Ask ten people what new wave is and ten different answers are sure to follow.

Serge Denisoff, “Tarnished Gold,” 107.

What is New Wave?

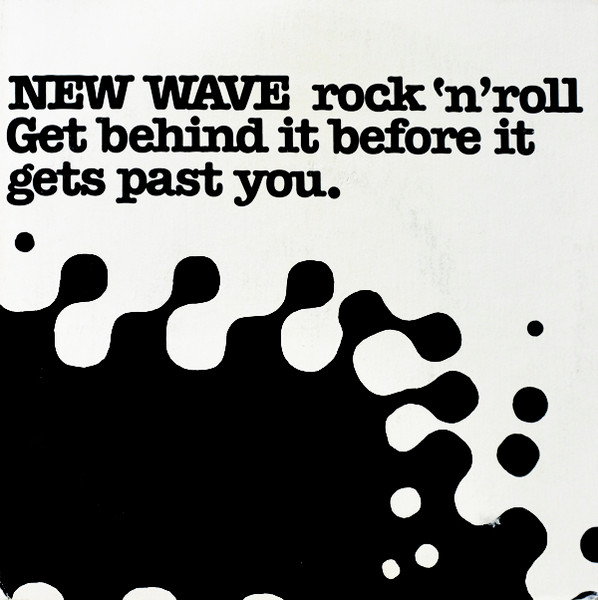

It’s kind of an odd question, one that seems too easy and too hard to answer at the same time. In the new wave ad campaign by Sire Records and Warner, bands considered punk and new wave were placed under the same umbrella.

In the late 1970s, music journalism often conflated punk with new wave, as publications wrangled with describing various scenes across the United States.

Scholars of music history have debated what exactly new wave is. Theo Cateforis, professor of music history and cultures at Syracuse University, wrote the most authoritative work on the subject, Are We Not New Wave?. Listen to Cateforis below talk about why the conflation between punk and new wave has been lost over time.

New Wave, New York

“Can this stuff sell? Or is this just an isolated New York scene?” asked Billboard in their cover story on the emerging punk scene in 1976.

The fine art scene in New York created an ecosystem of intimate clubs that attracted bands to play for small audiences. Each club had its niche, and each club found their own artists, bands, and audiences, allowing them to compete with one another.

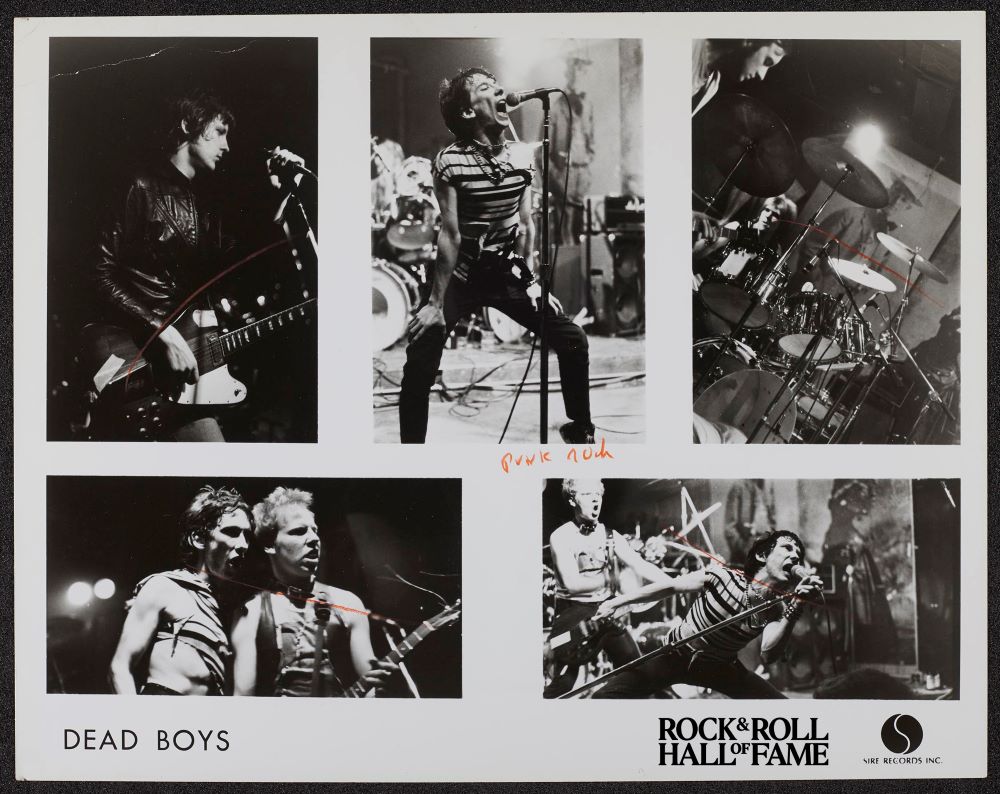

Despite the need for economic survival, these clubs were not afraid to have outlandish, crude performances. Such performance from bands like the Dead Boys have become synonymous with punk rock.

The sonic differences between these bands only compounded confusion. In the D.C.-area alternative newspaper Unicorn Times, writer Howard Wuelfing suggests that Talking Heads was apprehensive in taking on the new wave moniker due to its association with the Ramones.

“Talking Heads themselves are very wisely reluctant to openly admit kinship with the new wave phenomenon as misrepresented by the mass media. The images of leather and safety pinned, misogynist urchinry don’t fit or appeal to them one whit.”

Howard Wuelfing, “Talking Heads Approach Art Rock from the Right Direction,” Unicorn Times, January 1978.

“The Dead Boys, Cleveland’s own incisive contribution to the global village of the New Wave, are into scars. Not that their publicity hadn’t promised me as much — Dead Boys fans have reportedly made a practice of etching their heroes’ arms with cigarette burns, in punk salute…”

Richard Riegel, “Dead Boys Tell No Tales (Under An Hour, That Is),” Creem, February 1979.

Though new wave later would denote commercial value by means of how the music sounded, the fact that all of these bands were placed under the umbrella of new wave identifies what new wave meant as a term itself.

In this context, we can understand new wave as a term that is not only commercial but is commercial through vagueness, a value that gave the term ability to include Talking Heads, Blondie, Television, the Ramones, and the Dead Boys.

Sire Bows to Warner

Enter Seymour Stein, co-founder of Sire Records. Stein was originally apprehensive to sign the Ramones, he not only added the band to the label’s roster but expanded to numerous other bands in the scene. Although Stein is credited with proliferating and even coining the term new wave to describe this music, Warner Music Group was integral in new wave reaching a mass audience.

Warner Music Group had locked Sire into a distribution deal in 1977 and was responsible for the “Don’t Call It Punk” ad campaign. Warner, spearheaded by executive Stan Cornyn, created compilation sampler albums alongside the ads to reinforce the connections between bands.

Sire and Warner’s campaign to push the new wave label may have continued to conflate punk and new wave as synonymous with one another. But the campaign’s power lied in the executives and promoters that pushed this music to a mass audience.

That push, motivated by the tastes of people like Stein and others, at times created rifts between artists’ intent and the will of the music industry machine. Those rifts are highlighted throughout the artist profiles on this site.

What happened next?

Well, new wave, possibly because of the continued conflation with punk artists, failed to break radio. Thankfully, platforms like MTV swooped in to feature artists like Talking Heads. But the movement’s first wave of artists lost traction. Only a few artists culled from the Bowery succeeded into the ’80s.

Later, independent labels completely untethered to the majors laid the groundwork for music like grunge, which differed from the role majors like Warner played in cultivating new wave for a mass audience.